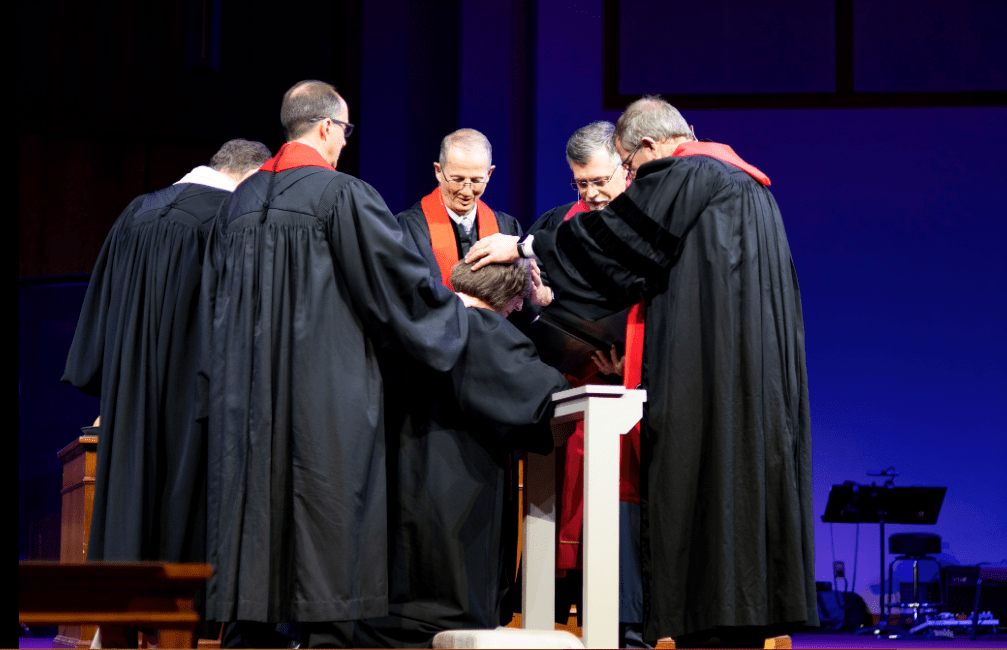

As I begin to write this, I am preparing to be ordained as an elder in the Global Methodist Church in about 36 hours. The longer I’ve pastored, the more I’ve realized that people—myself included—often don’t know the “why” behind many of the things we do as Methodists. I’ve found that answering the “why” question brings more clarity, meaning, and interest in our faith.

With that in mind, I’d like to try to briefly answer the question, “Why do we ordain in Methodism?” in a way that’s helpful and clear to all, Methodists and non-Methodists alike. I don’t claim to be an expert, merely someone who is traveling this path toward ordination with intrigue, curiosity, and a desire to help others see the “why” behind the “what.” I hope this helps!

The Bible is clear about many things. But it’s not clear about everything.

One of the things it’s not clear about is how to organize churches. One reason that it’s not clear on this is because, by the time the last book of our Bibles was being written, the early Christians were still trying to figure out how to organize churches. (Honestly, Christians are still trying to figure out how to organize churches even in the 21st century.)

Another reason it’s not clear on this is because different churches organized based on their location and the people in their church (this is called contextualization). What helped people connect with God and each other in one place didn’t work as well in another place, so they chose a different way to organize.

Maybe another reason the Bible isn’t clear on how to organize churches is because God wanted to give churches in every context over every generation the freedom to be able to choose how to best organize itself to fulfill the mission of God.

Still another reason is that the Christians who knew Jesus and the apostles believed that Jesus was coming back very soon (maybe even in their life times) and so the need for organization wasn’t as important or pressing.

One thing is clear, however: in the Bible and the early church, there was a need for leaders to be “set apart” to order the life of the church and ensure that the gospel being passed down from one generation to the next was the true gospel of Jesus Christ.

But before we get into those who are set apart, we have to talk about ministers.

The ministers of the church are… everyone.

Everyone who proclaims Jesus as Lord is a minister of the gospel of Jesus Christ. When God told the Israelites that they were to be a blessing to the nations, He didn’t give that command solely to the set-apart Levites; He gave that command to all Israelites. In the same way, when Jesus gave His Holy Spirit to empower His followers for ministry, He didn’t just give it to the apostles. He gave it to all of His followers.

We even have a rite in which we welcome people into the ministry of Christ, much like an ordination service. That rite is called baptism.

Ordination, therefore, isn’t about setting people aside for ministry. Rather, it’s about setting ministers apart to be leaders of ministers.

What those leaders are called to, though, doesn’t look like the leadership of this world. Rather, they’re called to diakonia, the Greek word for “service.” To lead the people of God, we serve the people of God.

There’s a long history of setting people apart for servant-leadership amongst the people of God. In the nation of Israel, God set apart the Levites to be a priestly order among His people. When Jesus came, He changed the qualifications of servant-leadership from bloodline to the gifts and call of the Holy Spirit. Jesus welcomed many followers but He chose twelve to set apart ministry.

Throughout Scripture, we see various models of church leadership, involving roles called “deacons” (diakonos), “elders” (presbyteroi), and “bishops/superintendents” (episkopos). How those roles functioned depended on the context in which they were in, but one thing was clear:

Some ministers were gifted and called by the Holy Spirit and commissioned by the Church to be set apart to lead the people of God.

This “set-apartness” is not an elevation of status or worth. Those who were and are set apart by God and the Church don’t become more loved, valued, or closer to God on account of their ordination. They don’t have God on speed dial just because they’re ordained.

Sometimes, we can be tempted to look at an ordained minister and think that they’re close to God on account of being in vocational ministry. Hopefully, they do walk in great alignment with God in all areas of their life. But right living and a vibrant relationship with God isn’t a result of ordination or being hired by a church, but rather, is a prerequisite to being set apart to lead the people of God.

A primary reason for this being a prerequisite is that ordained ministers represent the Church to the world. Thankfully, all ministers are representatives of Christ and the Church to the world (that’s how we’re able to reach people of all nations, languages, tribes, tongues, careers, socioeconomic classes, etc.) but when the world has doubt about what the Christian message and way of life is, they should be able to look at those who the Church has said “These people are gifted, called, and embody what it means to live in the way of Jesus” to see what that message and way of life is.

Over the two thousand years since the time of the earliest disciples, there have been many movements to distort the message of the gospel. Sometimes this has been intentional but other times this has been out of ignorance or out of the Church listening too much to culture than God Himself. To protect the Church against that, the Church ordains leaders to continue to carry on the Christian witness and to faithfully contextualize it in the time and place they find themselves.

Another important role of ordained ministers that most traditions accept is “sacramental authority,” meaning the authority to administer and preside over the sacraments. For Methodists, these sacraments are Holy Communion and Holy Baptism.

The reason only ordained ministers are given the authority to administer communion and baptism isn’t to separate the laity from the clergy or to create unnecessary “red tape” in the church. Rather, it’s because we view the sacraments so highly.

In Holy Communion, the essential elements of both Christian teaching and practice are brought together. Therefore, only those who have been called by God and commissioned by the church to uphold the truth of the gospel are allowed to be able to proclaim those truths through Holy Communion.

Holy Baptism is the entrance into the church. As a good shepherd only allows his sheep into the flock, someone set apart to be the shepherd of their church or ministry needs to ensure that those who are being welcomed into the church family (not the church doors, mind you… those are open to all) are people who are under the Lordship of the One True Good Shepherd. Otherwise, we risk division and injury to the sheep in the pen.

The Methodist movement—beginning as a reform movement in the Church of England (Anglican Church)—derived much of its polity (the way we organize our churches) from the Anglican Church.

We have two categories of ordained ministry in the expression of Methodism known as the Global Methodist Church: deacons and elders.

As the GMC’s Book of Doctrines and Discipline states, “Within the people of God, some persons are called to the ministry of deacon, which is a ministry of Word, Service, Compassion, and Justice” (¶503). Deacons can be called to many different areas of service, including pastoral ministry in a local church setting.

Elders are called to “the ministry of Word, Sacrament, and Order.” In the GMC, all elders start as deacons and “bear authority and responsibility to proclaim God’s Word

fearlessly, to teach God’s people faithfully, to administer the sacraments, and to order the life of the church so that it may be both faithful and fruitful” (¶503).

The last three days, I was at a conference where Kevin Watson, professor at Asbury Seminary and Wesley history extraordinaire, shared something I had never considered. In early American Methodism, preachers and those providing pastoral care were not the same people.

Preachers were ordained clergy who primarily rode on horseback on a circuit to preach to congregations, order the life of the church, resolve disputes, and preside over the sacraments. After that work was done, they would leave the area for weeks at a time. Pastoral care was then provided for by other ministers—the laity of the church.

What struck me about this is that ordination doesn’t put everything on the shoulders of the ordained ministers and it doesn’t release the laity from ministry. Ordination is a specific calling—an important one—but ministry happens from everyone in the church. If we are going to reclaim what God did in the early Methodist movement, I believe we’re in need of every Methodist stepping up to minister in and outside of the church.

As I was thinking about this blog post, Dennis M. Campbell’s book The Yoke of Obedience was extremely helpful in articulating all of this. I also think you should check out Kevin M. Watson’s Doctrine, Spirit, and Discipline.

Also, if you’re interested in subscribing to receive my posts via email, subscribe below:

And if you want to check out some of my previous posts, check them out here!

Leave a reply to Wholly Devoted to God and His Work – Hunter Bethea Cancel reply